MEN’S FASHION 1930

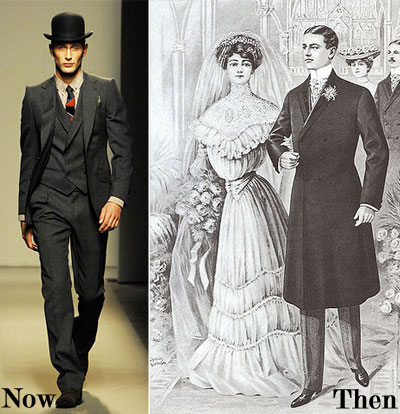

The decade of the 1930s saw dramatic changes in men’s fashion. It began with the great Wall Street Crash of October 24, 1929. By 1931, eight million people were out of work in the United States. Less or no work meant little or no money to spend on clothing. The garment industry witnessed shrinking budgets, and going-out-of-business sales were prevalent. The Edwardian tradition of successive clothing changes throughout the day finally died. Tailors responded to the change in consumer circumstances by offering more moderately priced styles.

In the early part of the decade, men’s suits were modified to create the image of a large torso. Shoulders were squared using wadding or shoulder pads and sleeves were tapered to the wrist. Peaked lapels framed the v-shaped chest and added additional breadth to the wide shoulders.

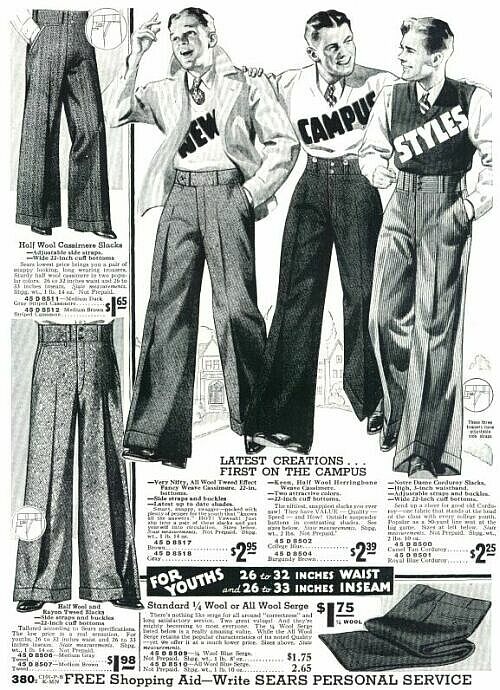

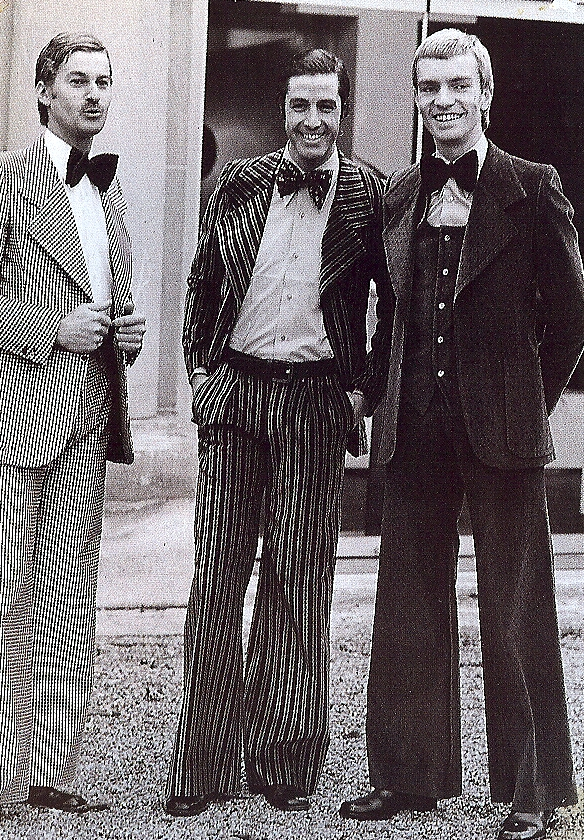

This period also was a rise in the popularity of the double-breasted suit, the precursor of the modern business suit. Masculine elegance demanded jackets with long, broad lapels, two, four, six or even eight buttons, square shoulders and ventless tails. Generous-cut, long trousers completed the look. These suits appeared in charcoal, steel or speckled gray, slate, navy and midnight blue.

Dark fabrics were enhanced by herringbone and stippled vertical and diagonal stripes. In winter, brown cheviot was popular. In spring, accents of white, red or blue silk fibers were woven into soft wool. The striped suit became a standard element in a man’s wardrobe at this time. Single, double, chalk, wide and narrow stripes were all in demand.

Plaids of various kinds became popular around this time as well. Glen plaid checks, originally known as Glen Urquhart checks from their Scottish origin, were one of the more stylish plaids. Glen plaid designs are sometimes referred to as “Prince of Wales” checks. Initially the design was woven in saxony wool and later was found in tweed, cheviot, plied and worsted cloth. (See glossary for definitions of these terms.)

In 1935, as a result of President Roosevelt’s New Deal, signs of prosperity returned. The rebounding economy demanded a redesign of the business suit, to signal the successful status of the man who wore it. This new look was designed by the London tailor, Frederick Scholte and was known as the “London cut”. It featured sleeves tapering slightly from shoulder to wrist, high pockets and buttons, wide, pointed lapels flaring from the top rather than the middle buttons and roll, rather than flat lapels. Shoulder pads brought the tip of the shoulder in line with the triceps and additional fabric filled out the armhole, creating drape in the shoulder area. As a result of this last detail, the suit was also known as the “London drape” or “drape cut” suit.

Other versions of the new suit included four instead of six buttons, lapels sloping down to the bottom buttons, and a longer hem. This version was known as the Windsor double-breasted (D.B.) and the Kent double-breasted (D.B.), named after the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Kent respectively. Clark Gable, Jimmy Stewart, Fred Astaire and Cary Grant were a few of the Hollywood stars who lent their endorsement to this style by wearing the suits in their movies. From there it became popular in mainstream America.

The famous “Palm Beach” suit was designed during the 1930s. It was styled with a Kent double or single-breasted jacket, and was made from cotton seersucker, silk shantung or linen. (See glossary for definitions.) Gabardine was also used to make this suit. It quickly became the American summer suit par excellence and was touted as the Wall Street businessman’s uniform for hot days.

During this time, blazers became popular for summer wear. Blazers are descendants of the jackets worn by English university students on cricket, tennis and rowing teams during the late nineteenth century. The name may derive from the “blazing” colors the original jackets were made in, which distinguished the different sports teams. The American versions were popular in blue, bottle green, tobacco brown, cream and buff. Metallic buttons traditionally adorned the center front of the jackets, and they were worn with cotton or linen slacks and shorts

A discussion of men’s fashion during the thirties would be incomplete without recognizing the gangster influence. Gangsters, while despised as thieves, paradoxically projected an image of “businessman” because of the suits they wore. However, they didn’t choose typical business colors and styles, but took every detail to the extreme. Their suits featured wider stripes, bolder glen plaids, more colorful ties, pronounced shoulders, narrower waists, and wider trouser bottoms. In France, mobsters actually had their initials embroidered on the breast of their shirts, towards the waist. They topped their extreme look with felt hats in a wide variety of colors: almond green, dove, lilac, petrol blue, brown and dark gray. High-fashion New York designers were mortified by demands to imitate the gangster style, but obliged by creating the “Broadway” suit.

In 1931, “Apparel Arts” was founded as a men’s fashion magazine for the trade. Its purpose was to bring an awareness of men’s fashion to middle-class male consumers by educating sales people in men’s stores, who in turn would make recommendations to the consumers. It became the fashion bible for middle- class American men.

Over the next three decades, American garment makers rose to a new level of sophistication, successfully competing with the long-established English and French tailors. However, the eruption of war at the end of the decade brought an abrupt halt to the development of fashion all over the world.

On September 3, 1939, England and France declared war on Germany for invading Poland, and refusing to withdraw troops. Once again, men’s fashion would change as a result of historic events.

1930 GLOSSARY OF TERMS

Cheviot: A British breed of sheep known for its heavy fleece. Cloth produced from this wool is a heavy twill weave.

Gabardine: A firm, tightly woven fabric of worsted, cotton, wool or other fiber with a twill weave.

Glen plaid: Vertical and horizontal stripes intersecting at regular intervals to form a houndstooth check.

Herringbone: A pattern consisting of adjoining vertical rows of slanting lines suggesting a “V” or an inverted “V”. Also known as chevron.

Houndstooth check: A pattern of broken or jagged checks.

Saxony: A fine three-ply yarn. Cloth produced from the yarn is a soft-finish compact fabric.

Seersucker: Originally from India and named after a Persian expression, “shirushakar”, meaning milk and sugar. It is a rippled or puckered cloth resulting from the vertical alternation of two layers of yarn, one taut and one slack, which also creates the characteristic stripe.

Shantung: A plain weave silk cloth made from yarns with irregular or uneven texture.

Tweed: A coarse wool cloth in a variety of weaves and colors originally from Scotland. (Many tweeds are multi-color and textured.)

Twill weave: One of three basic weave structures in which the filling threads (woof threads) are woven over and under two or more warp yarns producing a characteristic diagonal pattern.

Worsted: Firmly twisted yarn or thread spun from combed, stapled wool fibers of the same length. Cloth produced from this yarn has a hard, smooth surface and no nap (like corduroy or velvet).

Written by Carol Nolan-Edited by Julie Williams

Share this:https://adrianasassoon.wordpress.com

flores que apresentam essa tonalidade. No mundo da moda a primeira criadora a utilizar este tom foi Elsa Schiaparelli, uma reconhecida estilista italiana que durante as duas guerras mundiais dominou, juntamente com Coco Chanel, a indústria da moda, tornando-as eternas rivais. A colaboração da italiana com artistas surrealistas como Salvador Dalí marcou a sua carreira, deixando para a posteridade pérolas como um vestido gigante com uma lagosta impressa ou ainda um chapéu gigante em forma de sapato. Chanel dirigia-se a Schiaparelli como “a artista italiana que faz umas roupas”. Yves Saint Laurent considerava-a e ao seu rosa-choque “uma provocação”. Actualmente, em termos cromáticos, a grande herdeira da irreverência de Schiaparelli é a espanhola Agatha Ruiz de la Prada. A criadora, conhecida como a fada fucsia, adora a tonalidade “porque é a cor das meias dos toureiros, ainda que seja anti-touradas”, confessou.Porque o fucsia não é um mero rosa, nem é um lilás, porque foi preciso um pouco de arte e de ciência para que esta cor existisse, aqui estou.

flores que apresentam essa tonalidade. No mundo da moda a primeira criadora a utilizar este tom foi Elsa Schiaparelli, uma reconhecida estilista italiana que durante as duas guerras mundiais dominou, juntamente com Coco Chanel, a indústria da moda, tornando-as eternas rivais. A colaboração da italiana com artistas surrealistas como Salvador Dalí marcou a sua carreira, deixando para a posteridade pérolas como um vestido gigante com uma lagosta impressa ou ainda um chapéu gigante em forma de sapato. Chanel dirigia-se a Schiaparelli como “a artista italiana que faz umas roupas”. Yves Saint Laurent considerava-a e ao seu rosa-choque “uma provocação”. Actualmente, em termos cromáticos, a grande herdeira da irreverência de Schiaparelli é a espanhola Agatha Ruiz de la Prada. A criadora, conhecida como a fada fucsia, adora a tonalidade “porque é a cor das meias dos toureiros, ainda que seja anti-touradas”, confessou.Porque o fucsia não é um mero rosa, nem é um lilás, porque foi preciso um pouco de arte e de ciência para que esta cor existisse, aqui estou.