Tarsila do Amaral

| Tarsila do Amaral |

|

| Birth name |

Tarsila do Amaral |

| Born |

September 1, 1886

Capivari, São Paulo, Brazil |

| Died |

January 17, 1973

São Paulo, Brazil |

| Nationality |

Brazil |

| Field |

Painter |

Tarsila do Amaral, (b. September 1, 1886 in Capivari, São Paulo,– d. São Paulo on January 17, 1973).

Tarsila do Amaral, known simply as Tarsila, is considered to be one of the leading Latin American modernist artists, described as “the Brazilian painter who best achieved Brazilian aspirations for nationalistic expression in a modern style.” She was a member of the Grupo dos Cinco (Group of Five), which included Anita Malfatti, Menotti del Picchia, Mário de Andrade, and Oswald de Andrade.

Biography Tarsila was born in the city of Capivari, part of the interior of São Paulo, Brazil, to a wealthy family who were coffee growers and landowners. Her family’s position provided her a life of privilege. Although women of privilege were not expected to seek higher education, her parents supported her educational and artistic pursuits. During her teens, Tarsila and her family traveled to Barcelona, where she attended school and first exhibited her interest in art by copying images seen in the school’s collections.

Beginning in 1916, Tarsila studied sculpture in São Paulo with Zadig and Montavani. Later she studied drawing and painting with the impressionist painter Pedro Alexandrino. These were all respected but conservative teachers. In 1920, she moved to Paris and studied at the Académie Julian and with Emile Renard. The Brazilian art world was conservative, and travels to Europe provided students with a broader education in the areas of art, culture, and society. At this time, her influences and art remained conservative.

Brazilian modernism

Returning to São Paulo in 1922, Tarsila was exposed to modernism after meeting Anita Malfatti, Oswald de Andrade, Mario de Andrade, and Menotti del Picchia. Prior to her arrival in São Paulo from Europe, the group had organized the Semana de Arte Moderna (“Week of Modern Art”) during the week of February 11-18, 1922. The event was pivotal in the development of modernism in Brazil. The participants were interested in changing the conservative artistic establishment in Brazil by encouraging a distinctive mode of modern art. Tarsila was asked to join the movement and together they became the Grupo dos Cinco, which sought to promote Brazilian culture, the use of styles that were not specifically European, and the inclusion of things that were indigenous to Brazil.

During a brief return to Paris in 1923, Tarsila was exposed to Cubism, Futurism, and Expressionism while studying with André Lhote, Fernand Léger, and Albert Gleizes. European artists in general had developed a great interest in African and primitive cultures for inspiration. This led Tarsila to utilize her own country’s indigenous forms while incorporating the modern styles she had studied. While in Paris at this time, she painted one of her most famous works, Le Negra (1923). The principal subject matter of the painting is a large negroid female figure with a single prominent breast. Tarsila stylized the figure and flattened the space, filling in the background with geometric forms.

Excited about her newly developed style and feeling ever more nationalistic, she wrote to her family in April 1923:

“I feel myself ever more Brazilian. I want to be the painter of my country. How grateful I am for having spent all my childhood on the farm. The memories of these times have become precious for me. I want, in art, to be the little girl from São Bernardo, playing with straw dolls, like in the last picture I am working on…. Don’t think that this tendency is viewed negatively here. On the contrary. What they want here is that each one brings the contribution of his own country. This explains the success of the Russian ballet, Japanese graphics and black music. Paris had had enough of Parisian art.”

Pau-Brasil period

Oswalde de Andrade, who had become her traveling companion, accompanied her throughout Europe. Upon returning to Brazil at the end of 1923,Tarsila and Andrade then traveled throughout Brazil to explore the variety of indigenous culture, and to find inspiration for their nationalistic art. During this period, Tarsila made drawings of the various places they visited which became the basis for many of her upcoming paintings. She also illustrated the poetry that Andrade wrote during their travels, including his pivotal book of poems entitled Pau Prasil, published in 1924. In the manifesto of the same name, Andrade emphasized that Brazilian culture was a product of importing European culture and called artists to create works that were uniquely Brazilian in order to “export” Brazilian culture, much like the wood of the Brazil tree had become an important export to the rest of the world. In addition, he challenged artists to use a modernist approach in their art, a goal they had strived for during the Semana de Arte Moderna.

During this time, Tarsila’s colors became more vibrant. In fact, she wrote that she had found the “colors I had adored as a child. I was later taught they were ugly and unsophisticated.” Her initial painting from this period was E.C.F.B.(Estrada de Ferro Central do Brasil), (1924). The painting represented the new railway that linked Rio de Janeiro to São Paulo, and contained many aspects of the industrial city, such as rail bridges, rail cars, telephone poles, and signals. In addition, however, she included other aspects that would make this modern scene a distinctly Brazilian one: the colorful houses, a colonial church, and palm trees and other vegetation. She combined cubism with vivid colors and tropical elements to create her own unique Brazilian style, featuring local landscapes and scenery. Furthermore, at the time, she had an interest in the industrialization and it’s impact on society.

Antropofagia period

In 1926, Tarsila married Andrade and they continued to travel throughout Europe and the Middle East. In Paris, in 1926, she had her first solo exhibition at the Galerie Percier. The paintings shown at the exhibition included São Paulo (1924), La Negra (1923), Lagoa Santa (1925), and Morro de Favela (1924). Her works were praised and called “exotic,” “original,” “naïve,” and “cerebral,” and they commented on her use of bright colors and tropical images.

While in Paris, she was exposed to surrealism and after returning to Brazil, Tarsila began a new period of painting where she departed from urban landscapes and scenery, and began incorporating surrealist style into her nationalistic art. This shift also coincided with a larger artistic movement in São Paulo and other parts of Brazil which focused on celebrating Brazil as the country of the big snake. Building on the ideas of the earlier Pau-Brasil movement, artists strove to appropriate European styles and influences in order to develop modes and techniques that were uniquely theirs and Brazilian.

Tarsila’s first painting during this period was Abaporu (1928), which had been given as an untitled painting to Andrade for his birthday. The subject is a large stylized human figure with enormous feet sitting on the ground next to a cactus with a lemon-slice sun in the background. Andrade selected the eventual title, Abaporu, which is an Indian term for “man eats,” in collaboration with the poet Raul Bopp. This was related to the then current ideas regarding the melding of European style and influences. Soon after, Andrade wrote his Anthropophagite Manifesto, which literally called Brazilians to devour European styles, ridding themselves of all direct influences, and to create their own style and culture. Instead of being devoured by Europe, they would devour Europe themselves. Andrade used Abaporu for the cover of the manifesto as a representation of his ideals. The following year the manifesto’s influence continued, Tarsila painted Antropofagia (1929), which featured the Abaporu figure together with the negroid figure from Le Negra from 1923, as well as the Brazilian banana leaf, cactus, and again the lemon-slice sun.

In 1929, Tarsila had her first solo exhibition in Brazil at the Palace Hotel in Rio de Janerio, and was followed by another at the Salon Gloria in São Paulo. In 1930, she was featured in exhibitions in New York and Paris. Unfortunately, 1930 also saw the end of Tarsila and Andrade’s marriage. This brought an end to their collaboration.

Late Career and Social Themes

In 1931, Tarsila traveled to the Soviet Union. While there, she had exhibitions of her works in Moscow at the Museum of Occidental Art, and she traveled to various other cities and museums. The poverty and plight of the Russian people had a great effect on her. Upon her return to Brazil in 1932, she became involved in the São Paulo Constitutional Revolt against the current dictatorship of Brazil, led by Getulio Vargas. Along with others who were seen as leftist, she was imprisoned for a month because her travels made her appear to be a communist sympathizer.

The remainder of her career she focused on social themes. Representative of this period is the painting Segundo Class (1931), which has impoverished Russian men, women and children as the subject matter. She also began writing a weekly arts and culture column for the Diario de São Paulo, which continued until 1952.

In 1938,Tarsila finally settled permanently in São Paulo where she spent the remainder of her career painting Brazilian people and landscapes. In 1950, she had an exhibition at Museum of Modern Art, São Paulo where a reviewer called her “the most Brazilian of painters here, who represents the sun, birds, and youthful spirits of our developing country, as simple as the elements of our land and nature…. Tarsila’s life is a mark of the warm Brazilian character and an expression of it tropical exuberance.”

Legacy

Besides the 230 paintings, hundreds of drawings, illustrations, prints, murals, and five sculptures, Tarsila’s legacy is her effect on the direction of Latin American art. Tarsila moved modernism forward in Latin America, and developed a style unique to Brazil. Following her example, other Latin American artists were influenced to begin utilizing indigenous Brazilian subject matter, and developing their own style.

Selected artworks

- An Angler, 1920’s, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

- Cuca, 1924, Museum of Grenoble, France

- Landscape with Bull, 1925, Private Collector

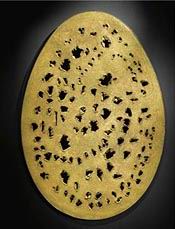

- El huevo, 1928, Gilberto Chateaubriand, Rio de Janeiro

- Abaporu, 1928, Eduardo Constantini, Buenos Aires

- Lake, 1928, Private Collection, Rio de Janeiro

- Antropofagia, 1929, Paulina Nemirovsky, Nemirovsky Foundation, San Pablo

- Sol poente, 1929, Private Collection, São Paulo

- Segundo Class, 1933, Private Collection, São Paulo

- Retrato de Vera Vicente Azevedo, 1937, Museu de Arte Brasileira, São Paulo

- Purple Landscape with 3 Houses and Mountains, 1969-72, James Lisboa Escritorio de Arte, São Paulo

Exhibitions

1922 – Salon de la Societe des Artistes Francais in Paris (group)

1926 – Galerie Percier, Paris (solo)

1928 – Galerie Percier, Paris (solo)

1929 – Palace Hotel, Rio de Janeiro (solo)

1929 – Salon Gloria, São Paulo (solo)

1930 – New York (group)

1930 – Paris (group)

1931 – Museum of Occidental Art, Moscow

1933 – I Salon Paulista de Bellas Artes, São Paulo (group)

1951 – I Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo (group)

1963 – VII Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo (group)

1963 – XXXII Venice Bienalle, Venice (group)

2005 – Woman: Metamorphosis of Modernity, Fundacion Joan Miró, Barcelona (group)

2005 – Brazil: Body Nostalgia, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Japan (group)

2006 – Salao of 31: Diferencas in Process, National Museum of Beautiful Arts, Rio de Janeiro (group)

2006 – Brazilian Modern Drawing: 1917-1950, Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro (group)

2006 – Ciccillo, Museum of Art Contemporary of the University of São Paulo, São Paulo (group)

2007 – A Century of Brazilian Art: Collection of Gilbert Chateaubriand, Museum Oscar Niemeyer, Curitiba (group)

Notes

- ^ Lucie-Smith, Edward. Latin American Art of the 20th Century. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2004: 42.

- ^ Damian, Carol. Tarsila Do Amaral: Art and Environmental Concerns of a Brazilian Modernist. Woman’s Art Journal 20.1 (1999): 3-7.

- ^ Damian, Carol. Tarsila Do Amaral: Art and Environmental Concerns of a Brazilian Modernist. Woman’s Art Journal 20.1 (1999): 3-7.

- ^ Lucie-Smith, Edward. Latin American Art of the 20th Century. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2004: 42.

- ^ Lucie-Smith, Edward. Latin American Art of the 20th Century. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2004: 44.

- ^ Damian, Carol. Tarsila Do Amaral: Art and Environmental Concerns of a Brazilian Modernist. Woman’s Art Journal 20.1 (1999): 3-7.

- ^ Damian, Carol. Tarsila Do Amaral: Art and Environmental Concerns of a Brazilian Modernist. Woman’s Art Journal 20.1 (1999): 5.

- ^ Damian, Carol. Tarsila Do Amaral: Art and Environmental Concerns of a Brazilian Modernist. Woman’s Art Journal 20.1 (1999): 7.

[edit] Sources and further reading

- Congdon, K. G., & Hallmark, K. K. (2002). Artists from Latin American cultures: a biographical dictionary. Westport, CT, Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313315442

- Lucie-Smith, Edward. Latin American Art of the 20th Century. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2004.

- Damian, Carol. Tarsila Do Amaral: Art and Environmental Concerns of a Brazilian Modernist. Woman’s Art Journal 20.1 (1999): 3-7.

- Barnitz, Jaqueline. Twentieth-Century Art of Latin America. China: University of Texas Press, 2006: 57.

- Gotlib, Nadia Batella. Tarsila do Amaral: a Modernista. São Paulo: Editora SENAC, 2000.

- Pontual, Roberto. Tarsila. Groves Dictionary of Art. Ed. Jane Turner. New York: Macmillan, 1996.

- Amaral, Aracy and Kim Mrazek Hastings. Stages in the Formation of Brazil’s Cultural Profile. The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts. 21 (1995): 8-25.

Share this:https://adrianasassoon.wordpress.com