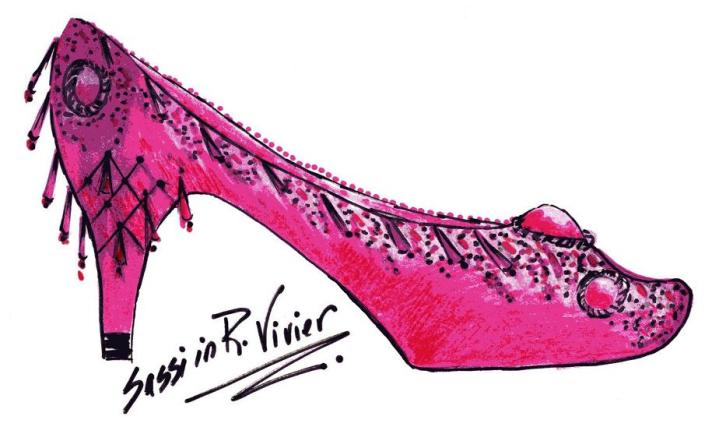

ROGER VIVIER by Adriana Sassoon ( sassisassoon)

Copyright © 2009 ADRIANA SASSOON .All Rights Reserved.

Copyright © 2009 ADRIANA SASSOON .All Rights Reserved.

WWW.HIREHEELS.COM

WWW.HIREHEELS.COM

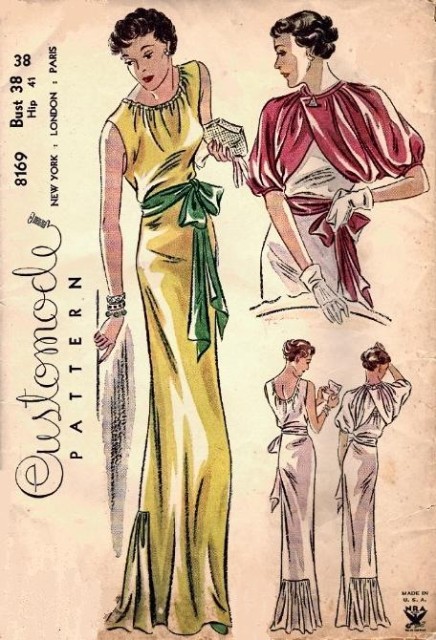

In the 1930s there was a return to a more genteel, ladylike appearance. Budding rounded busts and waistline curves were seen and hair became softer and prettier as hair perms improved. Foreheads which had been hidden by cloche hats were revealed and adorned with small plate shaped hats. Clothes were feminine, sweet and tidy by day with a return to real glamour at night.

The French designer Madeleine Vionnet opened her own fashion house in 1912. She devised methods of bias cross cutting during the 1920s using a miniature model. She made popular the halter neck and the cowl neck.

The bias method has often been used to add a flirtatious and elegant quality to clothes. To make a piece of fabric hang and drape in sinuous folds and stretch over the round contours of the body, fabric pattern pieces can be cut not on the straight grain, but at an angle of 45 degrees.

It is sometimes said that Vionnet invented bias cutting, but historical evidence suggests that close fitting gowns and veils of the medieval period were made with cross cut fabrics. The Edwardians also made skirts that swayed to the back by joining a bias edge to a straight grain edge and the result was a pull to the back that formed the trained skirt. She did really popularise it and the resulting clothes are styles we forever associate with movie goddesses and dancers like Ginger Rogers.

Using her technique designers were able to produce magnificent gowns in satins, crepe-de-chines, silks, crepes and chiffons by cross cutting the fabric, creating a flare and fluidity of drapery that other methods could not achieve. Many of the gowns could be slipped over the head and came alive when put on the human form. Some evening garments made women look like Grecian goddesses whilst others made them look like half naked sexy vamps. Certain of her gowns still look quite contemporary.

There was a passion for sunbathing. Women tried to get tans and then show them off under full length backless evening dresses cut on the true cross or bias and which moulded to the body. To show off the styles a slim figure was essential and that was getting easier for women who were educated and aware as many now used contraception and did not have to bear baby after baby unless desired.

The new improved fabrics like rayon had several finishes and gave various effects exploited by designers eager to work with new materials. Cotton was also used by Chanel and suddenly it was considered more than a cheap fabric for work clothes. But nothing cut and looked like pure silk and it was still the best fabric to capture the folds and drapes of thirties couture. Fine wool crepes also moulded to the body and fell into beautiful godets and pleats.

Schiaparelli liked new things as well as new ideas. In 1933 she promoted the fastener we call the zip or zipper. The metal zip had been invented in 1893 and by 1917 it was somewhat timidly used for shoes, tobacco pouches and U.S. Navy windcheater jackets. Her use of the new plastic coloured zip in fashion clothes was both decorative, functional and highly novel. They soon became universally used and are now a very reliable form of fastening.

Health and fitness was an important aspect of thirties lifestyle. As sun worshipping became a common leisure pursuit fashion answered the needs of sun seekers by making chic outfits for the beach and its surrounds. Beach wraps, hold alls, soft hats and knitted bathing suits were all given the designer touch.

Swimwear was getting briefer and the back was scooped out so that women could develop tanned backs to show off at night in the backless and low backed dresses. The colours of the beach holiday were navy, white, cream, grey, black and buff with touches of red.

Pyjamas introduced as informal dinner dress or nightwear for sleeping died quickly as fashions. However the third use of them as a practical beach outfit caught on and every woman made them an essential garment to pack. They were soon regarded as correct seaside wear. The trousers were sailor style, widely flared and flat fronted with buttons. They were made up in draping heavy crepe-de-chine. Blue and white tops or short jackets finished the holiday look.

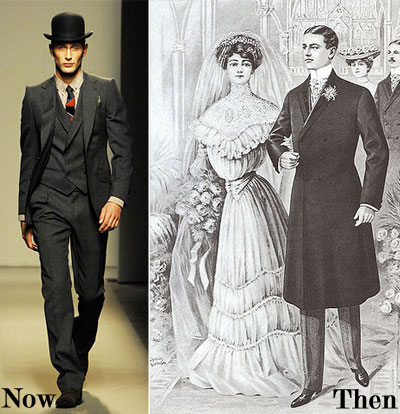

The decade of the 1930s saw dramatic changes in men’s fashion. It began with the great Wall Street Crash of October 24, 1929. By 1931, eight million people were out of work in the United States. Less or no work meant little or no money to spend on clothing. The garment industry witnessed shrinking budgets, and going-out-of-business sales were prevalent. The Edwardian tradition of successive clothing changes throughout the day finally died. Tailors responded to the change in consumer circumstances by offering more moderately priced styles.

In the early part of the decade, men’s suits were modified to create the image of a large torso. Shoulders were squared using wadding or shoulder pads and sleeves were tapered to the wrist. Peaked lapels framed the v-shaped chest and added additional breadth to the wide shoulders.

This period also was a rise in the popularity of the double-breasted suit, the precursor of the modern business suit. Masculine elegance demanded jackets with long, broad lapels, two, four, six or even eight buttons, square shoulders and ventless tails. Generous-cut, long trousers completed the look. These suits appeared in charcoal, steel or speckled gray, slate, navy and midnight blue.

Dark fabrics were enhanced by herringbone and stippled vertical and diagonal stripes. In winter, brown cheviot was popular. In spring, accents of white, red or blue silk fibers were woven into soft wool. The striped suit became a standard element in a man’s wardrobe at this time. Single, double, chalk, wide and narrow stripes were all in demand.

Plaids of various kinds became popular around this time as well. Glen plaid checks, originally known as Glen Urquhart checks from their Scottish origin, were one of the more stylish plaids. Glen plaid designs are sometimes referred to as “Prince of Wales” checks. Initially the design was woven in saxony wool and later was found in tweed, cheviot, plied and worsted cloth. (See glossary for definitions of these terms.)

In 1935, as a result of President Roosevelt’s New Deal, signs of prosperity returned. The rebounding economy demanded a redesign of the business suit, to signal the successful status of the man who wore it. This new look was designed by the London tailor, Frederick Scholte and was known as the “London cut”. It featured sleeves tapering slightly from shoulder to wrist, high pockets and buttons, wide, pointed lapels flaring from the top rather than the middle buttons and roll, rather than flat lapels. Shoulder pads brought the tip of the shoulder in line with the triceps and additional fabric filled out the armhole, creating drape in the shoulder area. As a result of this last detail, the suit was also known as the “London drape” or “drape cut” suit.

Other versions of the new suit included four instead of six buttons, lapels sloping down to the bottom buttons, and a longer hem. This version was known as the Windsor double-breasted (D.B.) and the Kent double-breasted (D.B.), named after the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Kent respectively. Clark Gable, Jimmy Stewart, Fred Astaire and Cary Grant were a few of the Hollywood stars who lent their endorsement to this style by wearing the suits in their movies. From there it became popular in mainstream America.

The famous “Palm Beach” suit was designed during the 1930s. It was styled with a Kent double or single-breasted jacket, and was made from cotton seersucker, silk shantung or linen. (See glossary for definitions.) Gabardine was also used to make this suit. It quickly became the American summer suit par excellence and was touted as the Wall Street businessman’s uniform for hot days.

During this time, blazers became popular for summer wear. Blazers are descendants of the jackets worn by English university students on cricket, tennis and rowing teams during the late nineteenth century. The name may derive from the “blazing” colors the original jackets were made in, which distinguished the different sports teams. The American versions were popular in blue, bottle green, tobacco brown, cream and buff. Metallic buttons traditionally adorned the center front of the jackets, and they were worn with cotton or linen slacks and shorts

A discussion of men’s fashion during the thirties would be incomplete without recognizing the gangster influence. Gangsters, while despised as thieves, paradoxically projected an image of “businessman” because of the suits they wore. However, they didn’t choose typical business colors and styles, but took every detail to the extreme. Their suits featured wider stripes, bolder glen plaids, more colorful ties, pronounced shoulders, narrower waists, and wider trouser bottoms. In France, mobsters actually had their initials embroidered on the breast of their shirts, towards the waist. They topped their extreme look with felt hats in a wide variety of colors: almond green, dove, lilac, petrol blue, brown and dark gray. High-fashion New York designers were mortified by demands to imitate the gangster style, but obliged by creating the “Broadway” suit.

In 1931, “Apparel Arts” was founded as a men’s fashion magazine for the trade. Its purpose was to bring an awareness of men’s fashion to middle-class male consumers by educating sales people in men’s stores, who in turn would make recommendations to the consumers. It became the fashion bible for middle- class American men.

Over the next three decades, American garment makers rose to a new level of sophistication, successfully competing with the long-established English and French tailors. However, the eruption of war at the end of the decade brought an abrupt halt to the development of fashion all over the world.

On September 3, 1939, England and France declared war on Germany for invading Poland, and refusing to withdraw troops. Once again, men’s fashion would change as a result of historic events.

Cheviot: A British breed of sheep known for its heavy fleece. Cloth produced from this wool is a heavy twill weave.

Gabardine: A firm, tightly woven fabric of worsted, cotton, wool or other fiber with a twill weave.

Glen plaid: Vertical and horizontal stripes intersecting at regular intervals to form a houndstooth check.

Herringbone: A pattern consisting of adjoining vertical rows of slanting lines suggesting a “V” or an inverted “V”. Also known as chevron.

Houndstooth check: A pattern of broken or jagged checks.

Saxony: A fine three-ply yarn. Cloth produced from the yarn is a soft-finish compact fabric.

Seersucker: Originally from India and named after a Persian expression, “shirushakar”, meaning milk and sugar. It is a rippled or puckered cloth resulting from the vertical alternation of two layers of yarn, one taut and one slack, which also creates the characteristic stripe.

Shantung: A plain weave silk cloth made from yarns with irregular or uneven texture.

Tweed: A coarse wool cloth in a variety of weaves and colors originally from Scotland. (Many tweeds are multi-color and textured.)

Twill weave: One of three basic weave structures in which the filling threads (woof threads) are woven over and under two or more warp yarns producing a characteristic diagonal pattern.

Worsted: Firmly twisted yarn or thread spun from combed, stapled wool fibers of the same length. Cloth produced from this yarn has a hard, smooth surface and no nap (like corduroy or velvet).

Written by Carol Nolan-Edited by Julie Williams

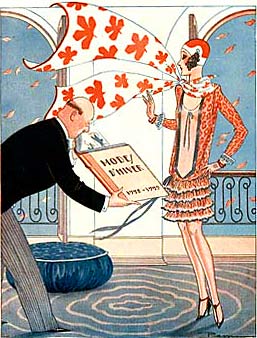

Various social trends were at work during the 1920s. Historians have characterized the decade as a time of frivolity, abundance and happy-go-lucky attitudes. In 1920, women got the right to vote, and a year earlier, alcohol had become illegal. World War I had just ended. The 1920’s would mark the first youth revolution, long before the 1960’s.

Young people were very indignant after World War I, and felt the older generation had just murdered millions of young boys. So they stopped obeying conventional rules and invented their own liberated culture: driving their own cars, and drinking, and petting with people they weren’t married to. And, for the first time in history, older women started copying younger women. In the late 19th Century, younger women wanted to look like grownups. Now, for the first time, everyone wanted the thinness and relative bosomlessness of early adolescence. People felt free-spirited and wanted to have fun. As a result, fashions became less formal. The biggest phenomenom of the 1920’s was the worship of youth.

The feminine liberation movement had a strong effect on women’s fashions. Most importantly, the corset was discarded! For the first time in centuries, women’s legs were seen. Women wanted to be “smarty” and/or freewheeling. Talking about Freud and sex were signs of hipness. Young men, “the flaming youth,” wore raccoon coats and drove around in old used Model Ts. Black-influenced jazz music and dance styles (ie. the Charleston and the Black Bottom) captivated white youth to the dismay of their parents. Dating, as we know it today, was invented in the 1920s. Previously, boys had to be courting a girl, they had to be committed, and girls had to be engaged to them in order to go out with them. The unchaperoned date was something new. Dating permitted people to see each other, and discover each other without having to proclaime an intent to marry. When flappers and flaming youth got together, the results was explosive. Petting was a popular and well received pastime for the youth. It allowed a girl to have erotic interaction without endangering herself with an unwanted or out of wedlock child. Petting could mean kisses or fondling, but it stopped just short of intercourse, and while parents equated petting with fornication, teenagers did not, and their peer group would still accept them and respect them. Intimacy and eroticism was explored. “Petting Parties,” where eager, youthful hands explored the nether regions of the opposite sex, was standard college entertainment. “Billing and cooing” (that is, to “bill and coo”) was to whisper sweet nothings while “making whoopee.”

The flapper was the heroine of the Jazz Age. She was the culmination of all the trends of the 20’s. With short hair and a short skirt, rolled hose and powdered knees – the flapper must have seemed like a rebel to her mother (the gentle Gibson girl of an earlier generation). No longer confined to home and tradition, the typical flapper was a young women who was often thought of as a little fast and maybe even a little brazen. She defied conventions of acceptable feminine behavior. The flapper was “modern.” Traditionally, women’s hair had always been worn long. The flapper wore it short, or bobbed. She used make-up (which she might well apply in public). She wore baggy dresses which often exposed her arms as well as her legs from the knees down. Strings of pearls trail from her shoulder or are knotted at the neck and thrown over the right shoulder or under the arm. Silver bracelets are worn on her upper arm. Flappers did more than symbolize a revolution in fashion and mores they embodied the modern spirit of the Jazz Age.

1920s fashion, though, was about so much more than fringed flapper dresses and feathered headbands, the cliche that many people associate with the era. As with every decade, the ’20s had its fads as well as its classics, a few of which live on today. It was a romantic era for fashion, which is why people look back at this era with great fondness and still emulate its style. The era set the standard for the modern concept of beauty. The modern supermodel’s figure, is — itself modeled after the 1920’s ideal of a woman’s figure (that of a thin pre-pubesent girl on the verge of puberty). The central phenomenom of the era was the worship of youth. For the first time in history, older women started copying younger women.

The pre-pubesent girl look became popular, including flattened breasts and hips, and bobbed hair. Fashions turn to the “little girl look” in “little girl frocks”: curled or shingled hair, saucer eyes, the turned-up nose, bee-stung mouth, and de-emphasized eyebrows, which emphasize facial beauty. Shirt dresses have huge Peter Pan collars or floppy bow ties and are worn with ankle-strap shoes with Cuban heels and an occasional buckle. Under wear is fashionable in both light colors and black, and is decorated with flowers and butterflies. With the cult of youth and the new spirit of equality come the camisole knickers; also fashionable is no underwear at all. Along with the rage for drastic slimming, women still strive to flatten their breasts and de-emphasize their hips. The cult of the tan begins; lotions to prevent burning and promote tanning appear on the market. Skin stains are also manufactured, as well as moisturizers, tonics, cream rouges, eye shadows, and more varied lipstick shades.

In the 1920s, a lot of clothing was still made at home or by tailors and dressmakers. The brand-name, ready-to-wear industry didn’t really exist until the 1930s, however some ready-made clothing was available from department stores and mail-order catalogs. Several magazines devoted to sewing were sources for patterns, transfers and appliques by mail. However, improved production methods enabled manufacturers to easily produce clothing affordable to working families. Because of this, the average person’s fashion sense became more sophisticated.

In 1923, the boyish bobbed hair transforms into the shingle cut, flat and close to the head, with a center or side part. A single curl at each ear is pulled forward onto the face. New felt cloche hats appear with little or no decoration in colors that match the day’s dress. Hats are pulled down to the eyes, and their brims are turned up in the front or back. In clothing, the straight line still emphasized the pre-pubesent look, but fabrics are now embroidered, striped, printed, and painted, influenced by Chinese, Russian, Japanese, and Egyptian art. Oriental fringed scarves, slave bangles, and long earrings were set off. Artificial silk stockings, later called rayon, are stronger and less expensive that real silk ones, although they are shiny. The new seamless stocking, despite its wrinkling, also makes the leg look naked. At bedtime, girls wear pajama bottoms, halter tops, and boudoir cape to protect their new hairdos.

By 1926, women were wearing skirts, shortest of the decade, stopping just below the knee with flouncing pleats; they are worn with horizontal-striped sweaters and long necklaces. Short and colorful evening dresses have elaborate embroidery, fringes, futuristic designs, beads, and appliques. The cocktail dress is born. The new sex appeal extends from the bee-stung mouth and tousled hair to a new focus on legs, with silk stocking rolled around garters at rouged knees. The “debutante slouch” emerges: hips thrown forward, as the woman grips a cigarette holder between her teeth. Mothers and daughters are flappers, many nearly nude beneath the new, lighter clothing.

Daywear

There were two important ethnic influences on the fabric and prints of the 1920s. One was a Chinese influence, with kimono-styling, embroidered silks, and the color red. The discovery of King Tut’s tomb brought a rash of Egyptian fashion and and accessories, including snake bracelets that encircled the upper arm. Small floral and geometric prints were prevalent throughout the decade, especially toward the latter half.

Evening Wear

Contrary to popular belief, women didn’t always wear fringed flapper dresses with feathered bandeaux and a long strand of beads. There were many other styles of evening dresses.

Evening clothes were made of luxurious fabrics — mostly silks — in velvets, taffetas and chiffon. In the mid-1920s, sleeveless silk chiffon dresses were were often embellished with elaborate beadwork. Dresses were designed to move while dancing. Some had long trailing sashes, trains or asymmetric hemlines. Typically, women did not wear hats for evening, but instead wore fancy combs, scarves and bandeaux.